No response returned

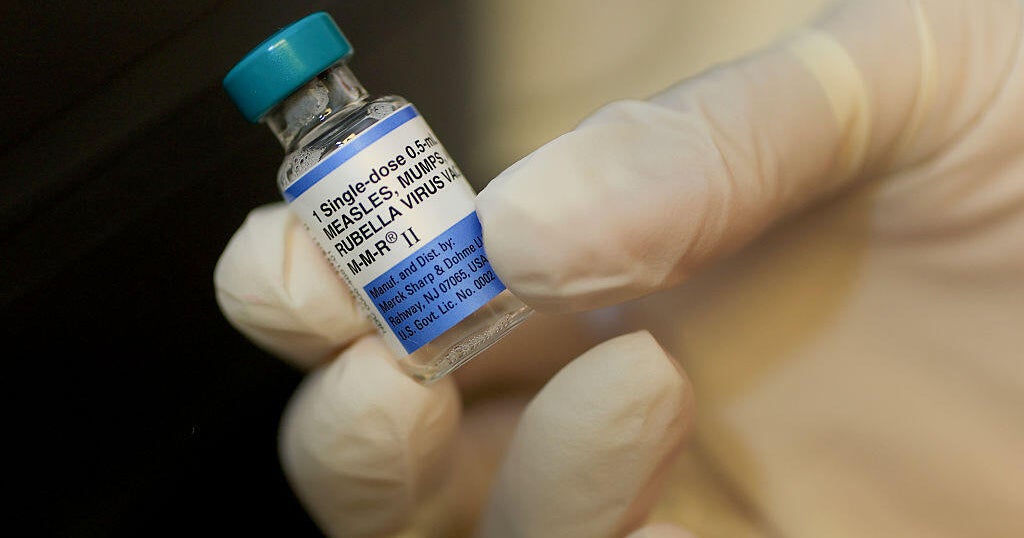

President that combination childhood vaccines, including the measles, mumps and rubella, or MMR, shot, should be separated marks a sharp break from decades of immunization practice in the United States.

"I was shocked," said Dr. William Moss, executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. "Those vaccines don't even exist in the U.S."

Moss said he hadn't heard such a recommendation "since the Andrew Wakefield days," referring to the former doctor whose 1988 autism study was later .

Investigations revealed Wakefield had undisclosed financial interests in both lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers and a single-measles vaccine patent. His license to practice medicine was revoked.

Mr. Trump's remarks also drew in Wakefield himself. In a video posted on social media, he said the president was "adopting the very recommendation that I made back in 1998," when he first called for splitting the MMR vaccine into individual components.

"This is a return to a discredited strategy," Moss said. "Wakefield had a financial stake in undermining MMR, and the science has never supported his claims."

The stakes of splitting a combination vaccine are not abstract, Dr. Howard Markel, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and medical historian, said.

"The immunization schedules are very carefully worked out so the vaccines have the most immunogenicity at the right age," he explained. "If you start splitting things up, you create barriers. Parents don't always come back, or they pick and choose, and coverage goes down. It's as simple as that."

Dr. Peter Hotez, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and vaccine expert at the Baylor College of Medicine, argued that the call to split vaccines is part of a broader campaign to discredit vaccinations.

"Every couple of weeks, there's a new zinger: first , then , then , now splitting MMR," he said. "Eventually, this topples the whole vaccine infrastructure like a house of cards."

The medical risks of dismantling the MMR schedule are clear. Measles remains one of the in circulation, capable of igniting outbreaks wherever vaccination rates dip. Rubella infection during pregnancy can cause congenital rubella syndrome, leaving babies with deafness, blindness or heart defects. Mumps, too often dismissed as mild, can lead to infertility in adolescent males.

The programmatic consequences are equally significant. Moss pointed out that parents already complain about too many injections. Splitting MMR into separate shots would increase both the number of visits and the number of needles children face, while weakening protection against rubella and mumps.

Every extra appointment creates barriers, especially for families with limited resources, Markel said.

Dr. Walt Orenstein, a former head of CDC's immunization program, described combination vaccines as the foundation of modern prevention.

"Combination vaccines were developed to reduce missed opportunities, increase coverage and minimize the trauma of multiple injections," he said. "Undoing that progress would put children at risk."

Measles-only vaccines also don't exist in the U.S. You can't walk into a pediatrician's office or retail pharmacy and ask for a standalone shot.

To make a measles-only vaccine available in the United States, a manufacturer would need to wait for measles outbreaks to occur, in order to test the vaccine in new clinical trials. Then they'd have to submit data for FDA approval and build a production and distribution system essentially from scratch. With no market for monovalent measles vaccines, companies would also have to be convinced there was sustainable demand — something experts say is unlikely given the entrenched use of MMR.

Objections to combined vaccines are not new, UC Berkeley medical historian Elena Conis noted.

"Resistance to vaccines and concerns about the form and content of vaccines is as old as vaccination itself," she said. "And concerns about combined vaccines are as old as combined vaccines themselves."

She pointed out that even before Wakefield, parents in the 1970s were asking why they couldn't just get some vaccines separately, echoing debates over the DPT (Diphtheria, Tetanus and Pertussis) vaccine at the time.

New momentum to separate measles from the rubella component is also driven by a recurring myth: that the rubella vaccine "contains fetal parts." In reality, the rubella virus was originally grown in human fetal cell lines developed in the 1960s, which have been replicated ever since without further abortions.

During production, the virus is purified, leaving only trace DNA or protein fragments that are broken, biologically inactive, and present at levels far below natural background levels in food or the human body. Regulators such as the Food and Drug Administration confirm these levels are safe. Advocates for separating MMR often conflate this history with the false claim that vaccines contain fetal tissue. Decoupling rubella is presented as a moral corrective, even though it introduces practical barriers and undermines protection for pregnant women and babies.

Conis also emphasized that resistance often depends on how people perceive the seriousness of each disease.

The public didn't always see the various infections as equal, Conis noted. At times rubella drew more fear than measles or mumps.

Mumps in particular, she said, "was often treated with humor rather than fear, until the MMR vaccine came along and researchers began to highlight complications like infertility and hearing loss."

Japan offers a cautionary example. In the early 1990s, Japan withdrew the combined MMR vaccine following concerns about the safety of its mumps vaccine and reverted to measles-only shots. The result was lower uptake of rubella and mumps vaccines compared to measles, leaving gaps in protection.

Decades later, Japan has faced repeated rubella outbreaks, including epidemics in 2013 and 2018-2019 that sickened thousands and led to cases of congenital rubella syndrome. Because of earlier policies that vaccinated only girls against rubella, large cohorts of adult men remain under-immunized, forcing costly catch-up campaigns and leaving Japan vulnerable to epidemics.

Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and vaccine expert at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, warned splitting up the MMR vaccine would repeat past mistakes.

"We've been here before. Andrew Wakefield promoted single-antigen vaccines, and it nearly derailed measles control in the U.K. The science was fraudulent, but the damage was real: thousands of kids went unprotected. To revive that model in 2025 is to repeat one of the most damaging chapters in vaccine history."

Columbia University historian James Colgrove noted that this kind of backlash has deep roots.

"The original anti-vaccination movement in the 19th century was really a movement against state coercion," he said. "That's always been the paradox of compulsory vaccination: it's extremely effective, but it's also one of the most likely to trigger backlash."

Conis framed the debate in broader terms of autonomy and mandates.

"There's always been a tension in vaccination between individual choice and public health," she said. "Parents are asked to give up some autonomy for the promise of better health for the population. For some, that's acceptable. For others, individual freedom matters more, and what's different today is that we're seeing the libertarian approach gain support at the highest levels of government."

Colgrove added that policymakers face a delicate balance. "The non-medical exemptions absolutely make laws more politically acceptable and are really key to diffusing backlash," he said. "At the same time, the broader your exemption, the more people you allow to opt out, then the more you risk compromising herd immunity. So it really is threading the needle."

And for Offit, the bigger danger is the pattern of misinformation itself.

"These claims aren't new; they're recycled," he said. "Once doubt takes root, it's extraordinarily hard to restore public confidence."

Research from multiple countries shows that combination vaccines improve uptake and timeliness by reducing missed appointments and the number of injections required. Children receiving combination formulations are more likely to complete their full schedule on time, and low-income parents are less likely to fall behind when multiple protections are delivered in a single shot.

For Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, a former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's immunization program who recently resigned, the proposal reflects politics rather than science.

"This isn't about safety. It's about ideology," he said. "We've already seen directives issued without data to back them up."

Dr. Debra Houry, who recently resigned as the CDC's chief science and medical officer, echoed the concern.

"The talk about separating MMR into individual components wasn't coming from scientists," she said. "It was being driven by political operatives with no public health expertise."

According to Moss: "It's not necessary, and monovalent vaccines aren't even available in the United States. There's no reason to go down that path."